- matthewgregorowski

- Aug 22, 2024

- 5 min read

On the foothills of Table Mountain lies a desolate patch of land where a vibrant and cosmopolitan community once thrived. To its 60,000 former Muslim, Cape Malay and Xhosa inhabitants it was the heartbeat of Cape Town. And as the South African Government tore it down, to the millions of onlookers both home and abroad it became the shameful symbol of racist oppression.

As Dad points out, it’s some 50 years since the bulldozers left and it’s still mostly an abandoned wasteland. As if no-one dared touch it, or try to cover the scars. Perhaps it’s out of respect, or simply that we should never forget.

There’s a familiar melancholy in his voice, because we’ve talked about it many times. As if he is back behind the makeshift desk signing a petition to Prime Minister B. J. Vorster for District Six’s coloured residents to be included in the redevelopment. Having been declared a whites-only zone under the legislated Group Areas Act, despite less than 1% of the population being white, they were being relocated to a sandy, bleak township 25 kilometers away called the Cape Flats.

He never did hear back from the Office of the Prime Minister, nor his local MP. But he relishes in the fact that the pockets of District Six which survived are once again occupied by their original families. As are the few blocks of flats which did eventually get erected. He calls it a victory for the people, and yet another failure for the racist Nationalist State. Despite the party having long been consigned to the scrapheap of history he still relives these victories remorsefully, as if he could have done more. But that’s just his nature, his cross to bear.

Thankfully, at 80 years old his shoulders are still broad and his back still strong, thanks to his Friday morning hikes up Table Mountain. Now he gets to look down on the new South Africa that he fought so selflessly to bring about. Its many scars still run deep, but despite Nelson Mandela’s discarded legacy there is an unyielding sense of hope in South Africa. Because that is the nature of its colourful and stoic people.

I don’t recall my birthplace. I was still too young when mum and dad packed up our orange VW Beetle and headed for Bredasdorp, near the southern tip of Africa. But somehow all these years later, I can’t help feel that the plight of the good people of District Six is my cross to bear, also. And that I, too, should not allow those that do remember, to forget.

From the ashes…

In 1867, the area was originally named the Sixth Municipal District of Cape Town, housing slaves after their emancipation by the British. After large areas were razed to the ground at the turn of the 19th century following an outbreak of the bubonic plague, new buildings arose and flourished, creating a lively community of former slaves, artisans, merchants and other immigrants. Most populous among them were the Cape Malay people, known most fondly for their penchant for cooking.

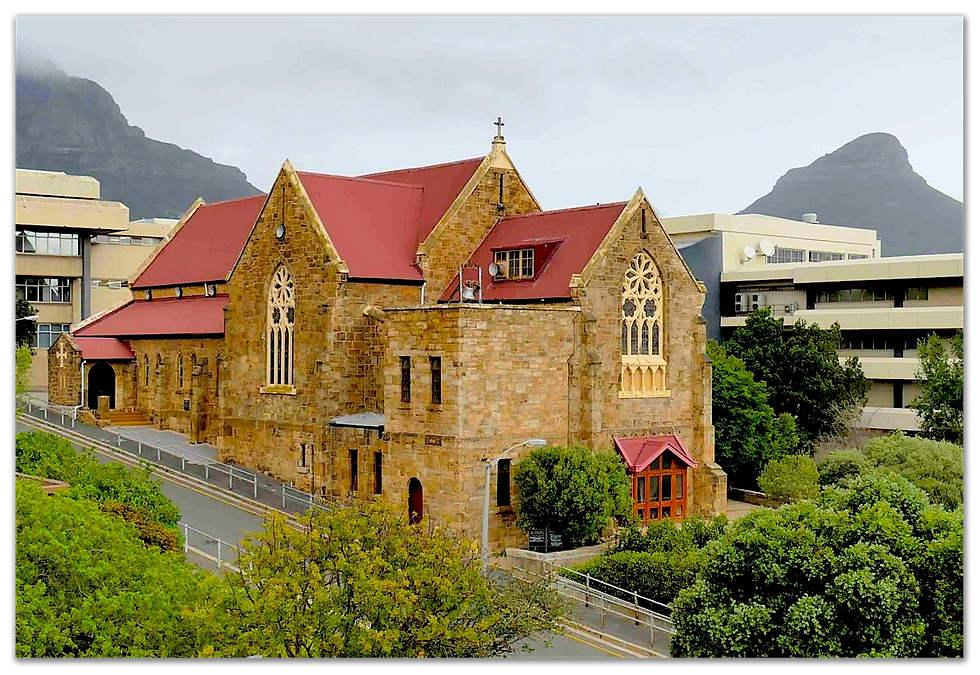

That same year saw the construction of St Mark’s Church with its infamous sandstone walls and shiny red roof, which to many former residents still stands as a beacon of hope. The Apartheid Government had offered to rebuild it stone for stone in the Cape Flats. But the people flatly refused, returning the two million Rand in compensation and instead vowing to get up every Sunday morning before dawn to make the long trek back to their rightful Church and home. It’s a tradition that continues to this day, only many of them now come from much further afield - to honour their undertaking, and that of their parents.

Dad was posted to St Mark’s in 1974, and when I was born a year later the young priest and his wife were overwhelmed with offerings of chicken biryani, mutton curry, bobotie (baked minced meat covered in egg) and koeksisters (deep fried dough soaked in syrup). For my arrival was truly a cause for celebration, as only the wondrously eclectic people of District Six knew to bestow.

In return, the energetic parish priest threw himself boldly into their arms – and they were all too willing to have him. It was a love affair that lasted less than four years thanks to not much being left standing, but he talks about it as a watershed time in his ministry. Standing in the pulpit, he would look down at his congregation and say, ‘You know, I really love you,’ and mean it, finally understanding how God could love each and every one of us.

As their numbers dwindled, he’d been tasked with uniting St Mark’s and St Phillips, District Six’s only other Anglican Church and bastion among the rubble of beaten up townhouses and poverty-scuffed alleyways. But what he quickly realised was that having lost nearly everything else, the last thing these good people needed was to lose the Church. What they needed was for him to befriend them, to accept them and to love them, and he did that with fervour.

Freedom is starving

When our VW Beetle putted away for the last time in 1977, our coloured nanny Cathy Whiteman carrying me in her arms in the back seat, it was a sobering time for mum and dad. They both sensed they had been part of something special, which they would never see the likes of again. But what they didn’t know then, was that it was a necessary part of their journey. And that the nostalgia they still carry was to become the bedrock of their lifelong dedication to serving the people of South Africa.

It is as friends and spiritual leaders that their hundreds of parishioners still remember them fondly today. They were more than just figureheads, they were the lifeblood of their communities. Because despite all the hardships, and there were many, everything they did came from a place of deep-rooted love and compassion. The same love and compassion that saw Dad treating burn victims in the townships of Grahamstown as a theological student.

Winter nights in the Eastern Cape townships were bitterly cold and most people lived in huts made of wood off-cuts and sheets of corrugated iron. Fires were the only way to keep warm, while paraffin lamps were used for light, so blazes broke out with alarming frequency. Each took more than its fair share of homes before being brought under control, one bucket of water from the communal tap at a time, when the water was running.

The Grahamstown Fire Department could only watch from the periphery as there was no way to get through or past the connected shacks in their fire tenders. So it was, donning his black cassock, that among the smouldering ruins, Dad would carry out his gauze and salve ministry.

As his compassion grew, so did his determination to act in defiance of the regime. It began with his fellow Rhodes University students, staging dawn to dusk hunger protests against racial segregation, with a simple message to the Government - 'Freedom is starving'. And culminated many years later in multi-denominational protest marches from St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town. Congregants who spilled into the streets after Sunday Eucharist would often be greeted by the Special Branch with their water cannons at the ready. A tactical unit of the South African Police Force, the Special Branch’s sole mission was to suppress anti-apartheid activism. They acted with impunity, widespread torture and detention as well as countless assassinations getting swept under blood-stained carpets.

But the worse things got, the more the people responded, the Church always leading from the front. From St George’s Cathedral, bishops and clergy would march arm in arm down Queen Victoria Street, their black and white cassocks flowing together in the stiff Cape southeaster, chanting ‘Apartheid won’t live forever but we will – bring back free will!’

And where were they headed? Why, to the place that had become synonymous with the struggle, of course. To my birthplace, and the place where a piece of Mum and Dad’s hearts still remain, beating in unison with the many thousands of beautiful people who still call it their home.